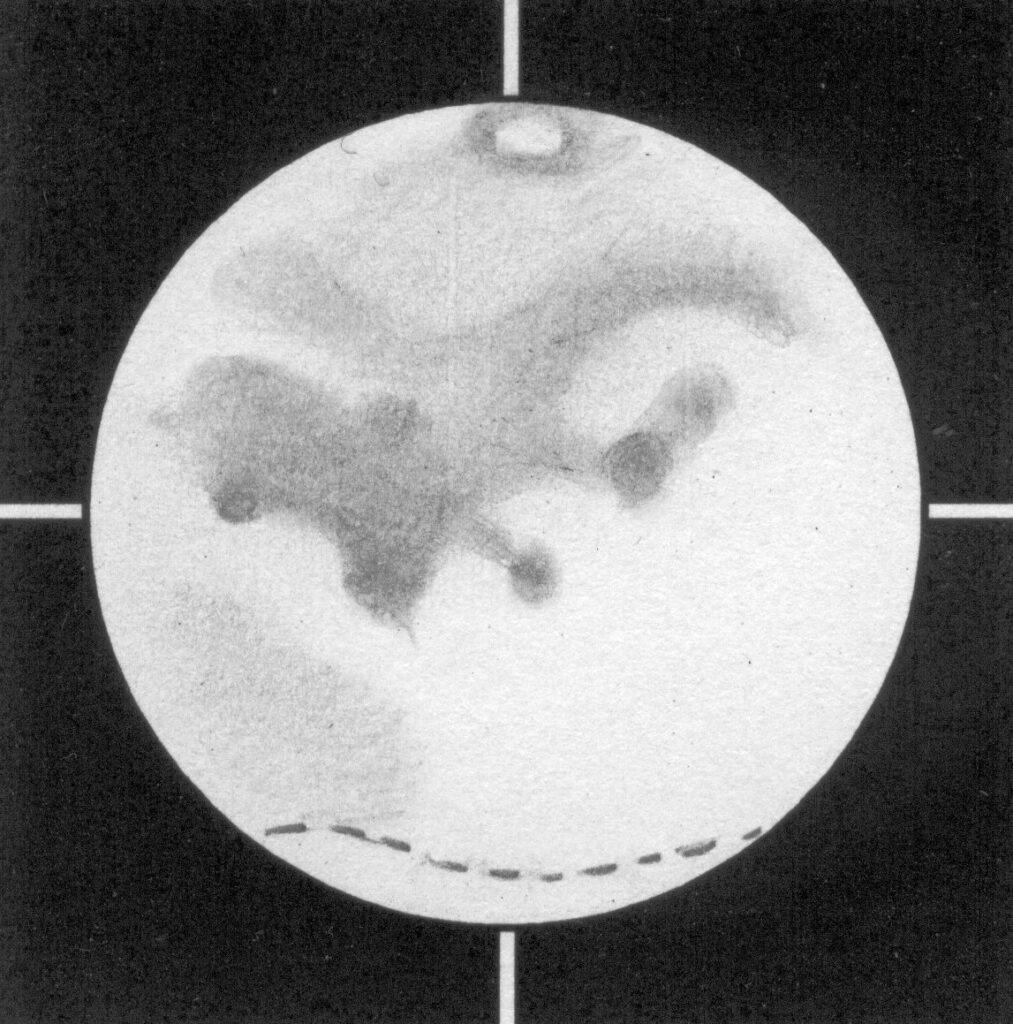

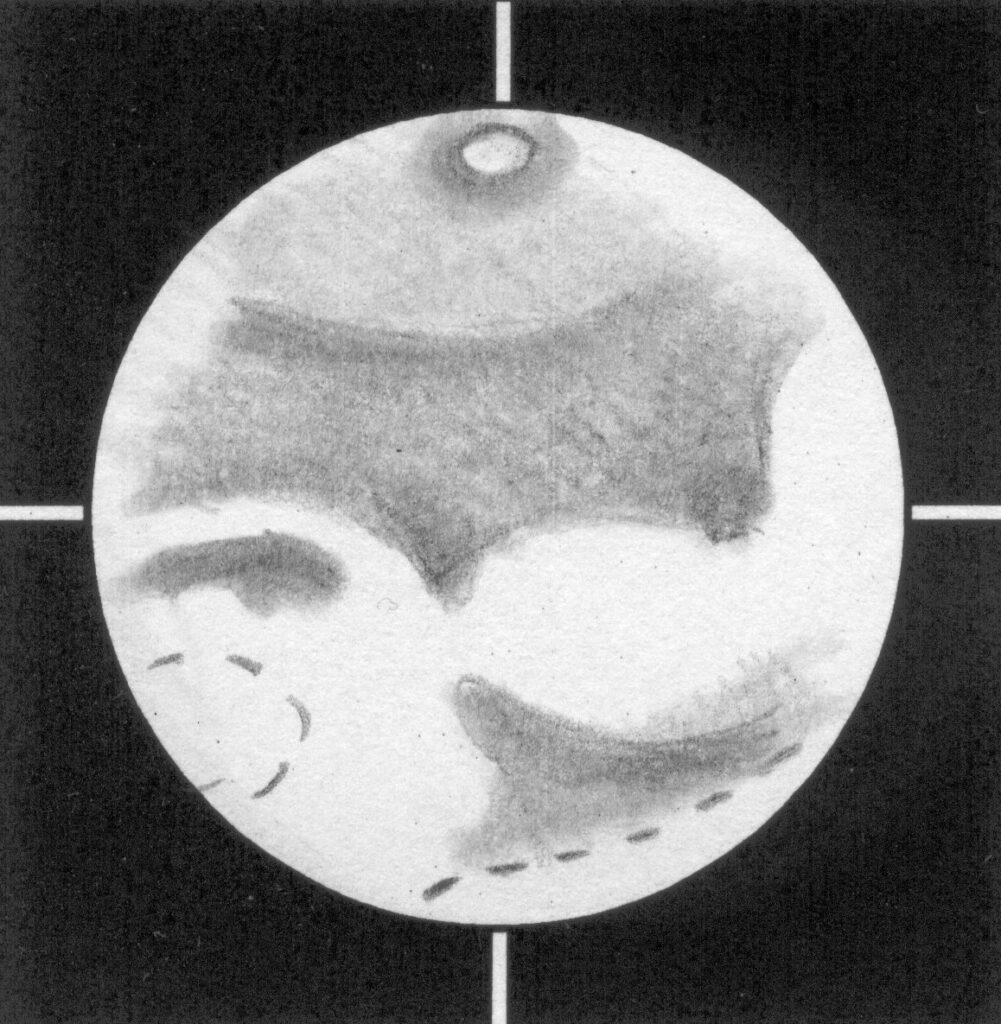

Mars as seen in a 120mm refractor at 382x with binoviewer in October 2020.

With the best apparition in decades, observing Mars now is fun in every respect – especially if you push your instrument to the maximum magnification.

Mars can be an intriguing target for visual astronomers when it is so big in the sky as now. But most observers follow outdated rules about maximum power and stay shy of really using the capacity of their telescopes. With Mars, this will cost the best part of what can be actually seen.

Follow the rules?

Most observers know certain rules of how to determine the maximum power of their telescope. When googling this topic you can find some of them:

- maximum power is 2x the telescope’s aperture in mm (e.g. 240x with a 120mm scope)

- maximum power is 50x aperture in inches, or even only 20x to 30x per inch (235x or 94x to 141x with a 120mm scope)

Other rules include

- avoid exit pupils below 0.4mm (would be 300x with 120mm)

- use the lowest high power possible

More sophisticated sources will explain that any magnification that gives a power above the resolution limit of the telescope is called “empty” and useless. Unfortunately, these sources will only know the Rayleigh or Dawes limits. But these limits determine the resolution of point sources (stars), and not extended surfaces as planets.

Have a closer look

To resolve the airy disc of a star in perfect seeing, a minimum magnification of aperture in mm/0.7 is needed. For my 120mm refractor, this would be 171x. Only when applying this power, your eyes will be able to resolve the Dawes limit of 0.97 arcsec with this scope.

But planets are different. They do not display a single airy disk. Instead, a lot of airy disks overlap and create a more detailed image, to which stellar resolution limit rules do not apply. There are empirical studies that show that in order to see a dark line of 0.1 arsec width on bright background, 23/aperture in mm give an idea of what can be resolved. My 120mm scope will thus show a 0.19 arcsec line.

These extremely small features must be magnified enough to be perceptible to the human eye! The basic rules cited above give magnifiactions that are far too low. With a high quality apochromatic refractor, magnifications of up to 3x per cm aperture can be reached in ideal conditions. Given a perfect telescope and a skilled observer, the only factor that actually will prevent this is atmospheric turbulence, colloquially known as “seeing”.

Planets are defying the rules

Seeing is dependent on telescope aperture surfcace. It will affect smaller telescopes much less, while larger apertures need better conditions. A 60mm telescope will be able to reach its limits four times as often as a 120mm aperture. But still the potential to resolve much finer details as the 60mm scope stays within its capability.

Most people tend to use a power that still renders a “sharp” image. I would like to encourage to go further: Even if the image does not look as good and is a bit soft, and turbulence is destroying definition most of the time, your eye will be able to make out more fine detail in the milliseconds of calm air as when looking at the sharper image at lower power. This requires a certain amount of patience, in many cases you’ll have to wait several tens of minutes to get glimpses of fine detail. But it will pay off eventually.

Actually, there is no such thing as “empty” or useless magnification. Discard all obsolete rules! In my exerience …

… with 60-70mm high quality apo a power of 3x aperture in mm is possible on 80% of nights

… with 100-120mm high quality apo a power of 3x aperture in mm is possible on 50% of nights

… with 200-250mm visually optimized reflector a power of 3x aperture in mm is possible on 10% of nights

Get the right eyepiece

But there is an unexpected problem: There are no suitable eyepieces for short focal ratio telescopes on the market. With a f/7.5-telescope, 3x aperture in cm will need an eyepiece of 2.5mm focal length. Unfortunately, the 2.5mm Nagler T6 has been discontinued, as has been the 2.5mm Pentax XO and the excellent 2-4mm Nagler Zoom. Remaining are the Vixen HR series with 1.6mm, 2.0mm, 2.4mm, and 3.4mm respectively, but they as well have been discontinued partially and only some focal lengths remain available.

I would not recommend using a Barlow lens instead. Look out for those short focal length eyepieces on the used market. This effort is worth it, though – to reach out for the power to unveil the full planetary detail your telescope is capable to show.